The mechanisms underlying cognitive impairments seen in people with HIV likely involve a combination of complex immunopathological processes controlled by HIV factors, the direct effects of cART and other host factors (e.g. age, lifestyle, comorbidities, polypharmacy). Given this complexity a holistic, multifaceted approach to assessing the primary causes and contributing factors of an individuals cognitive symptoms is required.

Current guidelines focus on identifying and managing HIV factors, and broadly neglecting the wider clinical, psychological and social factors which may be causing or compounding difficulties. Having a comprehensive understanding of the causes is essential to managing a patient with cognitive impairment. With this in mind, we recommend HIV services co-ordinate the assessment of the following six areas.

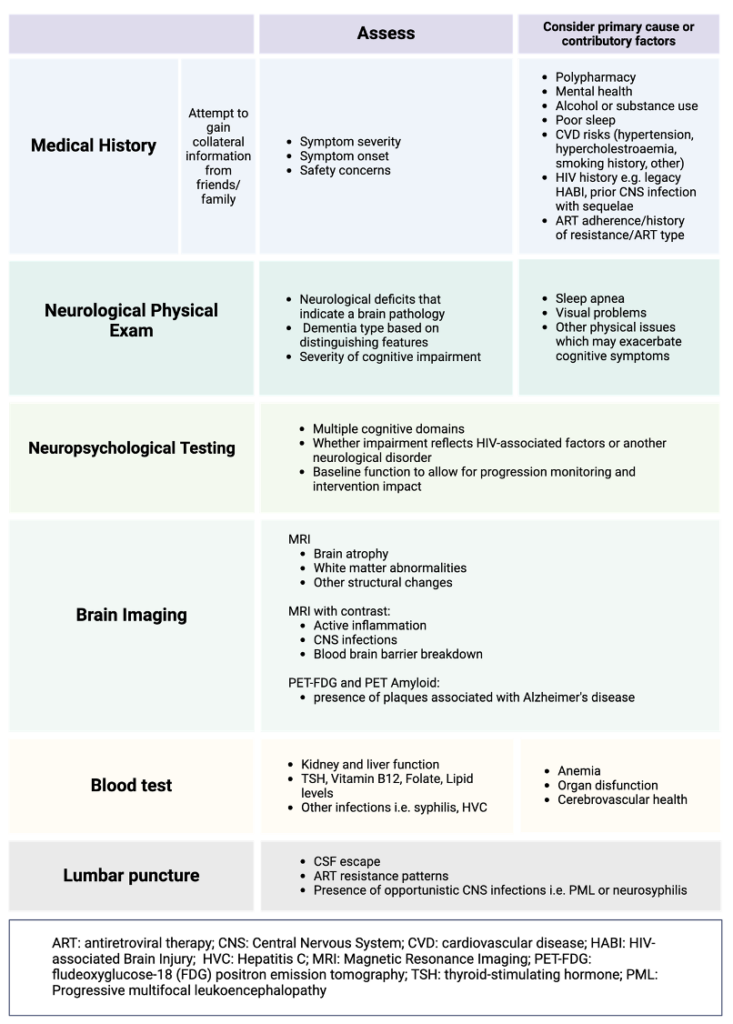

Please see the table at the end for a summary.

Please note that these are recommendations not guidelines, and clinical judgement should be applied accordingly.

For people with HIV experiencing cognitive symptoms, a comprehensive medical history essential to identify primary causes or contributing factors. Physicians should assess symptom onset, severity, and any safety concerns such as impaired judgment, difficulties managing daily activities or wandering. Additionally, polypharmacy, mental health issues, substance misuse, co-infections, and sleep patterns should also be explored.

Furthermore, it is crucial to determine if the symptoms are likely to be related to HIV-associated brain injury (HABI) or HIV cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) escape. Collateral information from family members or caregivers can provide vital insights into cognitive function, behavioral changes, and safety risks that patients may not report or be aware of.

A neurological physical examination is important in the context of cognitive impairment, particularly when dementia is suspected. This assists in identifying neurological deficits that may indicate underlying brain pathology, in distinguishing between types/causes of dementia and in assessing the severity of impairment.

It further aids in ruling out other neurological conditions that might present with similar symptoms. A general physical history and examination can also reveal factors such as sleep apnea, visual problems, or other physical issues that may contribute to or exacerbate cognitive symptoms.

Brain imaging, particularly Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), plays an important role in evaluating cognitive impairment in people with HIV. MRI provides detailed images of brain structures, detecting brain atrophy, white matter abnormalities, or other structural and vascular changes associated with cognitive decline.

MRI with contrast (gadolinium) is preferred, as it enhances visibility of active inflammation, CNS infections, blood-brain barrier breakdown, and tumors. MRI head without contrast is also useful, providing a detailed baseline view of brain’s structures and brain atrophy when suspected. If MRI is unavailable, a CT scan offers less detailed but still valuable information.

Advanced imaging, such as positron emission tomography-fludeoxyglucose (PET-FDG; a measures glucose metabolism in the brain), and PET amyloid (which allows the detection of amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease) can help distinguish between HIV-associated dementia and other neurodegenerative conditions.

Neuropsychological testing can provides more detailed information about cognitive functioning through its evaluation of specific cognitive domains such as memory, attention, executive functioning, language and visuospatial processing. This is essential for detecting subtle cognitive deficits that might not be evident in everyday functioning and can help to differentiate between cognitive impairment caused primarily by HIV from other neurocognitive disorders, which is critical for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Neuropsychological assessment can also help to establish baseline levels of cognitive functioning, monitoring progression and evaluating intervention effectiveness.

A comprehensive neuropsychological examination is optimal where cognitive difficulties are observed or reported, with a wide range of cognitive domains assessed using standardised assessment tools appropriate to the population. Although comprehensive neuropsychological batteries assess multiple cognitive domains, their implementation is often limited to larger clinical or research settings. Where comprehensive assessment is not possible or practicable, the use of a repeatable cognitive screening tool, such as the Montreal Cognitive Examination (MoCA) or the more comprehensive Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination (ACE-III) is recommended as a minimum.

Identifying subjective cognitive impairment and poor cognitive performance, even in the absence of overt symptoms, is equally important. Early identification facilitates proactive management and timely interventions, such as brain health interventions and teaching compensatory strategies which can improve day to day cognitive functioning. Moreover, the regular follow-up of individuals with objective and/ or subjective cognitive impairment enables preventive care, including interventions that may help to delay progression to more severe forms cognitive impairment. Examples of such interventions could include support to make lifestyle changes, manage psychological distress or reduce drug or alcohol misuse.

Lumbar puncture (LP) is helpful in assessing cognitive impairment in people with HIV, primarily to rule out cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) HIV escape and active HIV-associated brain injury (HABI). A matched blood sample for HIV RNA should be taken the same day, and CNS HIV RNA should be genotyped to detect resistance patterns differing from blood samples. LP also aids in diagnosing CNS opportunistic infections like progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and neurosyphilis, both of which can cause cognitive decline.

CSF biomarkers such as neurofilament light chain (NFL), neopterin, amyloid Aβ42-to-Aβ4, and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) offer insights into axonal injury and inflammatory processes, helping distinguish HIV-associated dementia from other conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. However, not all cognitive impairment cases require an LP: when impairment is clearly due to factors like substance abuse or severe depression prioritising the management of these underlying issues should be the primary focus. In uncertain cases or when attempting to excluding HABI, LP remains a valuable tool to detect CSF HIV escape not easily identified through imaging or other diagnostic modalities.

What examinations should be conducted if a cognitive issue is suspected?

Figure from Alford et al (2024) Curr Opin Infect Dis, In Press